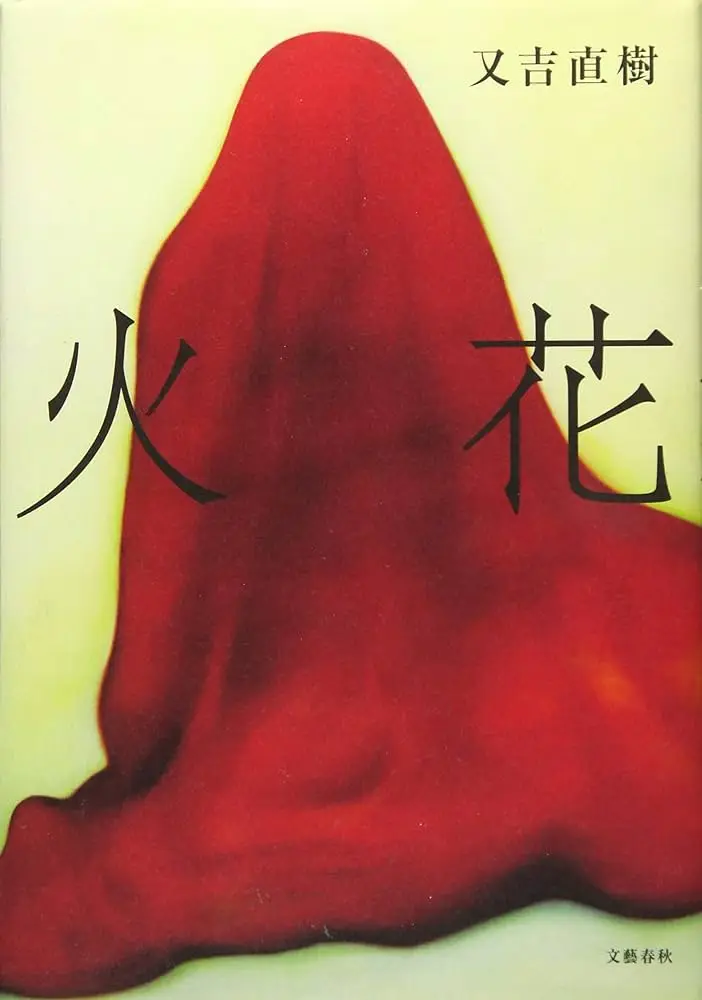

火花 (Hibana)

12 1月 2024

(cw: gender dysphoria discussion at the end of the book) haha, why am i crying

火花 (Hibana) was the first modern Japanese literary work I ever read[^1]. Before I encountered the mellifluous prose of Matayoshi Naoki in 2016, my knowledge of Japanese literature began with Murakami Haruki and ended with Natsume Souseki. Everything else I read, as older readers may remember, was visual novels and the occasional light novel.

I was not prepared for this book. It gave me a crash course in the aesthetics of Japanese literature. The book demanded that I throw out reductive writing advice like "show, don't tell" if I wanted to imagine the feelings and images it evoked. It was hard for me to ground myself in any scene, but the writing still aroused a sentimentality I had never felt before. I empathized with the isolation and idealism of the characters. It felt like I was getting two portraits of artists as young men in the 150 or so pages I read.

And yet, this book shouldn't have resonated with me as much as it did -- it came from the world of Japanese manzai comedy, a scene that remains profoundly alien to me to this day. I developed my sense of comedy through British sketch shows like Monty Python and the Flying Circus, and while there are parallels, it's not like I go out of my way to watch comedy shows today. The fact I even read this book is quite baffling to me.

But I think it has captured a desire that I've always had: the innocent urge to ruin old beautiful worlds we see to create newer and more beautiful worlds.

The book opens with a fireworks festival in Atami:

大地を震わす和太鼓の律動に、甲高く鋭い笛の音が重なり響いていた。熱海湾に面した沿道は白昼の激しい陽射しの名残りを夜気で溶かし、浴衣姿の男女や家族連れの草履に踏ませながら賑わっている。沿道の脇にある小さな空間に、裏返しにされた黄色いビールケースがいくつか並べられ、そこにベニヤ板を数枚重ねただけの簡易な舞台の上で、僕達は花火大会の会場を目指し歩いて行く人達に向けて漫才を披露していた。

We read that the taiko drums vibrate through the earth, the bright rays of the midday sun melt into the night sky, and crowds of people and families in yukata wander about.

But Tokunaga and his partner are trying to put on the best show they can on a stage of plywood piled on top of beer cans -- and they're also under a crushing time limit. Their jokes fall flat, Tokunaga's partner laughs hysterically at Tokunaga saying something like "I wouldn't want a parakeet to ask me if I'm alright", and they get the bird from the audience. As Tokunaga cries and laughs, imagining that he will respond to the parakeet by threatening to burn it, their performance is interrupted by the fireworks.

Tokunaga watches the fireworks[^2] and realizes that he needs a master to study under.

As he and his partner leave the stage, someone from the next duo tells Tokunaga that he will avenge them. This person goes on the stage, introduces his group as the あほんだら (Ahondara)[^3], stares at the audience as if picking a fight, and claims (in a stereotypical feminine voice) that he can sense whether people are going to heaven or hell by just looking at their faces. He points to the audience members and says, "Hell, hell, hell...". At one point, he even points to a young girl holding hands with her mother and says she's going to hell but a fun one before apologizing and condemning everyone else to hell.

The organizers don't like what just happened, but Tokunaga finds himself drawn to this person's antics. He is dragged to a local pub by this troublemaker and a few lines later is convinced that this person should be his mentor.

Unfortunately, his mentor is prone to misunderstanding. Few people find his jokes funny because they don’t sound like any other standard joke. In fact, they usually find him to be abrasive.

That’s why Tokunaga likes him: he keeps it real, he does it for the art, he is a true comedian — and his name is Kamiya.

What follows are the misadventures of Tokunaga and Kamiya as they struggle, each in their own way, to make sense of their place in the comedy industry. Both suffer from having too pure a heart and an inability to let cynicism take over their minds. They just want to make people laugh.

But that turns out to be a difficult task: you can't make everyone chuckle at your own jokes. Comedy ages like milk, and you can't please everyone. The only joke you can write is your own, which makes you vulnerable to the audience.

However, as Kamiya says, true comedy can only come from the heart. Only Tokunaga can make the jokes that Tokunaga will make, and the same goes for Kamiya. If they lose confidence in their own identities, then their jokes will just be superficial commercial stuff. As one can imagine, their dedication isn't exactly the kind that makes people buy tickets.

But Kamiya believes that the best manzai comedians are the ones who don’t push themselves and effortlessly become someone like a vegetable stall owner:

「準備したものを定刻に来て発表する人間も偉いけど、自分が漫才師であることに気づかずに生まれてきて大人しく良質な野菜を売っている人間がいて、これがまず本物のボケやねん。ほんで、それに全部気づいている人間が一人で舞台に上がって、僕の相方ね自分が漫才師やいうこと忘れて生まれて来ましてね、阿呆やからいまだに気づかんと野菜売ってまんねん。なに野菜売っとんねん。っていうのが本物のツッコミやねん」

If a vegetable stall owner says that his goods are of high quality, he's playing the boke (funny man). If Kamiya's comedy partner goes on stage, forgets he's a comedian, and turns into one of those vegetable sellers, Kamiya might say, "What kind of vegetables ya selling?” This is the true tsukkomi, the true straight man foil to the comedic antics. We can learn from life and our surroundings to write our own jokes because comedy is derived from the substance of life. We can script and plan our jokes, but at the end of the day, comedy should be as organic as life itself.

And I think that's probably true of a lot of things in art. Art is indefinable, but it is first and foremost a medium of expression. If art becomes too rigid, then it doesn't feel as expressive. We use art to channel complicated feelings: the more we put our soul into it, the more we forget that we're doing art in the first place, the more powerful our expression will be.

But that will always be abrasive to a degree. There are many court jester-like figures in the history of art precisely because they try to be themselves in a world that demands conformity. Their remarks are hurtful and funny precisely because they know which parts of life suck. You have to make a fool of yourself somehow in order to say something meaningful to society.

That takes courage, something Tokunaga doesn't always have. He often wonders if he made the right decision in middle school to sacrifice everything to join the comedy scene. Nevertheless, he is committed to his vocation and cannot have it any other way.

Kamiya, on the other hand, seems to have the opposite issue. Due to his bad reputation, he moves from his hometown of Osaka to Tokyo and instead of taking the chance to start afresh, he becomes more reckless.

These two characters are not living stable lives in any sense of the word. No matter how much I sympathize with Tokunaga and think Kamiya is cool, their lives are something I try to avoid, especially in the creative industry I work in. They are struggling artists who refuse to bow to pragmatism.

And it is this stubborn idealism that makes their lives interesting and their jokes funny to read. I understand why Kamiya thinks Tokunaga's comedy is unique: when Tokunaga was younger, his heart ached when he saw his sister, whom he admired, panic during her piano recital at school and practice all night, angering their drunken father; their mother defended her actions and forced him to apologize by buying her a piano. This narration is only something Tokunaga can come up with.

This is especially true when it comes to Kamiya, who will get angry at anyone who is just going through the motions, because they are not taking their art seriously. A good portion of the book is devoted to fleshing out Kamiya's philosophy of comedy. His bombastic claims about disrupting the status quo rarely sit well with Tokunaga, even if he finds them interesting. For Kamiya, disruption isn't about upsetting the status quo for the sake of upsetting it -- that would just turn into another dickflinging contest organized by the status quo -- he instead values cultivating new critical ways of seeing things and believes these methods should be allowed to grow. Whether it's someone lazily playing drums or resisting the avant-garde, Kamiya's rage at this kind of boring conservatism resonates with me.

Which makes his fuckups all the more frustrating to me. Like Tokunaga, I admire Kamiya's foolish dedication to his art. However, his detachment from reality makes everyone around him and even his own art suffer.

The arc that speaks to me the most is when he introduces Maki, his girlfriend-but-not-really. Tokunaga thinks that the two of them act like spouses who have been through a lot, but he is uncomfortable with Tokunaga hanging out with other women. Worse, Kamiya is completely open about spending Maki's money with little or no care. Later in the book, Kamiya announces that Maki has finally found a boyfriend and is moving out. He needs Tokunaga's help: specifically, he wants Tokunaga to get an erection and stare at it, so he won't get too emotional about his ex and her boyfriend being nice to him.[^4] His reasoning? So he can laugh about it later.

But the real kicker -- and my favorite scene in the whole book -- comes after that:

それから、真樹さんとは何年も会うことはなかった。その後、一度だけ井の頭公園で真樹さんが少年と手を繫ぎ歩いているのを見た。僕は思わず隠れてしまった。真樹さんは少しふっくらしていたが、当時の面影を充分に残していて本当に美しかった。圧倒的な笑顔を、皆を幸せにする笑顔を浮かべていて、本当に美しかった。七井橋を男の子の歩幅に合わせて、ゆっくりと、ゆっくりと歩いていた。その子供が、あの作業服の男の子供かどうかはわからない。ただ、真樹さんが笑っている姿を一目見ることが出来て、僕はとても幸福な気持ちになった。誰が何と言おうと、僕は真樹さんの人生を肯定する。僕のような男に、何かを決定する権限などないのだけど、これだけは、認めて欲しい。真樹さんの人生は美しい。あの頃、満身創痍で泥だらけだった僕達に対して、やっぱり満身創痍で、全力で微笑んでくれた。そんな真樹さんから美しさを剝がせる者は絶対にいない。真樹さんに手を引かれる、あの少年は世界で最も幸せになる。真樹さんの笑顔を一番近くで見続けられるのだから。いいな。本当に羨ましい。七井池に初夏の太陽が反射して、無数の光の粒子が飛び交っていた。神谷さんは、「なんで、池に飛び込んで真樹を笑かさんかったんや」と言うかもしれない。だが、あの風景を台なしにする方法を僕は知らない。誰が何と言おうと、真樹さんの人生は美しい。あの少年は世界で一番幸せになる。その光景を見たのは、神谷さんと僕が、最後に上石神井のアパートへ行ってから、十年以上後になる。

More than ten years later, Tokunaga sees Maki walking hand in hand with a young boy and hides from their view. As he watches them go their way, he realizes that her life is pure and beautiful. Although Tokunaga is a nobody, he wants to affirm the goodness of her life. Their smiles are authentic: they are the purest expression of kindness and happiness. Tokunaga doesn't know anyone, let alone him, who could disrupt such a beautiful life. Kamiya might ask him to jump into the river to make her laugh, but Tokunaga doesn't think that's possible. Her life is too unspoiled for their brand of comedy. All he can do is envy her son who will have the happiest life he'll ever know.

I remember that scene and it affected me when I was in my early 20s because it's such a beautiful depiction of an adult envying the innocence of a child. Now that I'm in my 30s, reading that scene broke my heart. This is the perfect life that many people will never have, and Kamiya fucked up. And for all the talk about destroying beauty for the sake of art, Tokunaga admits that there's nothing more beautiful than what he just saw. I am reminded of how often people who read and write literature can be envious of people who are able to live simple, unadulterated lives. Maki was an exit from the comedy/creative life[^5] -- is the struggle to become a truthful comedian worth it?

It's hard to say: the book is surprisingly honest about its ambivalence. Matayoshi Naoki is a working comedian himself, and he doesn't mince words about how principles and reality are always at odds in the comedy scene. The world Hibana portrays makes you wonder how anyone can make other people laugh: it must take more than a miracle to make the crowd laugh with you.

He accomplishes this by never letting the novel wallow in too much scene setting. It is more than happy to jump forward in time to get to the next thing it wants to say; flashbacks are interspersed within scenes, and the way I am writing this review is not necessarily the way Matayoshi wants you to experience the book. The book is full of impressions of life as a comedian in Tokyo, sketches of Kamiya and Tokunaga getting wasted, and descriptions of how comedy talent agencies work. This is a symptom of Tokunaga's voice: Tokunaga is not highly educated, and the only condition Kamiya has if Tokunaga wants to be his student is to write a biography about him. Chronology and pacing are of little importance to Tokunaga (and Matayoshi Naoki): it's more important to write about the vibes surrounding the events than to build up to a scene and finally release all the emotions it contains.

When I first read this book, I couldn't wrap my head around it. I couldn't picture any scenes, just bright colors and loud sounds. There are named places, but they were a blur to me because I was not familiar with Tokyo. The dialogue between Tokunaga and Kamiya was the only thing that put me on solid ground. I can only navigate this labyrinth through the echoes of their laughter and sorrow.

Today, I can see the world vividly in my mind as long as I follow Tokunaga's stream of thoughts and how he experiences life. Matayoshi's writing is ebullient to say the least: he leads the reader's eye from memory to memory, letting us gaze at small but interesting details before moving on to the next as if we're being guided through a museum. This acute description of Tokunaga's phenomenological experiences is rewarding to me because I can see, for a moment, memories of Tokyo through the eyes of a lonely, awkward young adult. I recognize why he's so focused on some details over others because I'm "him" in that moment of time and space. When Tokunaga defers from narrating in the more conventional way, it's because he doesn't think the events in the scene are important -- it's what he takes away from it.

Tokunaga's conclusions and implications -- the takeaway, if you will -- are the bread and butter of this book. We learn so little about Tokunaga's outside world that some readers are put off by the writing, but that's why I find Naoki Matayoshi's writing so impressive these days: he draws attention to how Tokunaga develops his view of the world around him. As the years pass by, we see the naivete in his thoughts turn into low self-esteem and finally into a modicum of competence.

Kamiya's dogmatic approach to life stands in heavy contrast to Tokunaga's. His denial of the necessities of life makes him less admirable and more like a real doofus. Tokunaga's narration may be a bit too self-centered for his own good, but at least he recognizes that there is a world around him. Kamiya doesn't: he just wants to make people laugh and that's all he wants to do.

But he hasn't done that in ages. We don't see his disillusionment, only glimpses of it through Tokunaga's narration. Just how deep the hole goes remains hidden until the very end.

Explicit ending spoilers:

Which brings us to the penultimate scene: Tokunaga has retired from the comedy scene with a big bang, impressing his mentor, who broke up with him years ago due to creative differences. Tokunaga is happy that Kamiya finds his comedy acceptable after all these years.However, he learns that Kamiya ghosted his comedy partner and owes people a lot of money -- in fact, Kamiya is bankrupt. His partner says in fact that he got exhausted looking like he knows things in fromt of Tokunaga. What annoys Tokunaga the most however is that Kamiya has this innate ability to make people laugh and he just doesn't use it. Why not? This question haunts him, but he is overwhelmed by a feeling of nostalgia when Kamiya opens his arms to greet his old mentor.

Until Kamiya reveals he has large breasts:

「なんですか、それ」

僕は瞬きすることも忘れ、その不思議な物体を見つめていた

「Fカップです」と神谷さんは、両手で胸を支えるようにして、確かにそう言った。

「なにしてんねん」

こいつは何を考えているのだろう。

「どうせなら、大きい方が面白いと思って。シリコンめっちゃ入れてん」

この人は狂っているのだろうか。

Kamiya now has F-cup knockers because he had surgery to get silicone breast implants. He feels this surgery is necessary because he stopped thinking making a character was unnecessary -- it would be fun to make a character with big tits. In fact, he might even go on TV because look, it's a guy with F-cup boobs! Wouldn't that be funny?

When Tokunaga hears all this, he gets angry and thinks that Kamiya has lost his mind. Who the hell is going to laugh at a 30-year-old guy with big boobs? It's not entertaining at all. It's just fucking weird and offensive.

What's even more horrifying is that Kamiya seemed to know something was wrong: when he was laughing his ass off on the operating table, he told a staff member in the clinic that he was doing it for TV, and they were taken aback. That reaction spooked him. And now he's looking for validation from the one person who understands him. Was it funny? Would this character work on television?

Tokunaga responds with a level of candor that even surprises him:

「神谷さん、あのね、神谷さんはね、何も悪気ないと思います。ずっと一緒にいたから僕はそれを知ってます。神谷さんは、おっさんが巨乳やったら面白いくらいの感覚やったと思うんです。でもね、世の中にはね、性の問題とか社会の中でのジェンダーの問題で悩んでる人が沢山いてはるんです。そういう人が、その状態の神谷さん見たらどう思います?」

He knows that Kamiya doesn't mean anything bad because he's been with the guy for ages. He understands why Kamiya thinks a guy with breasts is funny. But what would people suffering from gender and sexuality issues think of him?

Kamiya admits that they might feel uncomfortable and his whole body starts shaking. Tokunaga continues:

「そうですよね。神谷さんには一切そんなつもりがなくても、そういう問題を抱えている本人とか、家族とか、友人が存在していることを、僕達は知ってるでしょう。全員、神谷さんみたいな人ばかりやったら、もしかしたら何の問題もないかもしれません。あるいは、神谷さんが純粋な気持ちで女性になりたいのであれば何の問題もないです。でも、そうじゃないでしょう。そういう人を馬鹿にする変な人がいるってことを僕達は、世間の人達は知ってるんですよ。神谷さんのことを知らない人は神谷さんを、そういう人と思うかもしれませんよ。神谷さんを知る方法が他にないんですから。判断基準の最初に、その行為が来るんやから。神谷さんに悪気がないのはわかってます。でも僕達は世間を完全に無視することは出来ないんです。世間を無視することは、人に優しくないことなんです。それは、ほとんど面白くないことと同義なんです」

Even if Kamiya doesn't mean any harm, there are many people (if not their families and friends) who have struggled with these issues. If everyone were like Kamiya or if Kamiya really wanted to be a woman, there would be no problem. But the world isn't like that: we know that there are people who make fun of people's gender dysphoria. Not everyone knows Kamiya, and they won't be able to see his good faith anyway; they'll just end up seeing him as another bad faith actor. Tokunaga emphasizes that Kamiya can't just ignore the world, because ignoring the world means not being kind to the people around us -- and that's the same as not being funny at all.

Kamiya cries and wants Tokunaga to stop. He admits he fucked up, but Tokunaga stresses that he's not reprimanding him:

「神谷さんに差別的な意識が一切ないのはわかってます。男が巨乳やったら面白いという発想と、性別を馬鹿にすることとは全然違うんです。そんなんわかってます。でも、一緒やと思われますよ。もしくは同質の不快感を与えてしまうんです。僕達が情報として持っているのか、潜在的な嫌悪があるのかわからへんけど、そういう僕達の中の微妙な差別意識と結びついて、神谷さんの行為は許されへんもんになるんです」

All he's saying is that even if there's a gulf of difference between a guy with big breasts and a mockery of sexuality, people are going to think they're the same thing or at least feel the same kind of discomfort. They won't let Kamiya off the hook no matter what.

Kamiya finally confesses that his inability to make anyone but Tokunaga laugh has gotten to him. His sense of identity was broken and he tried to find a way to be funny again, but he didn't know how. All he can do is regret his current actions...

But the book ends on a hopeful note: after this disastrous conclusion, the narration asserts that there are no bad endings -- only that life is still going on for these two innocent middle-aged men. We don't know what comes next for Tokunaga and Kamiya; we can only be satisfied that Tokunaga is still writing Kamiya's biography.

Hibana is a story about dreamers who can't stop dreaming, but it also makes us interrogate the value of those dreams. I can't help but think of Robert Pippin in After the Beautiful where he emphasizes that our judgments about art are connected to historical time and open to revision; Hibana is sensitive to this as these hopeless dreamers have to realize that they have to adapt to ever-changing conditions. When Kamiya says he wants to disrupt comedy, he is attacking current trends. Comedy (and art as a whole) is situational: it will speak differently when newer material conditions and tastes arrive. Like the sparks of a firework, dreams are not timeless but singular moments of awe and inspiration. No one dreams outside of time or in a vacuum; our hopeless dreams, which we continue to create, are situated in the societies in which we live. In order for our dreams to be relevant -- to be aspirational -- we must align them with the needs of our time.

That's a difficult path as any artist knows: it's easy to lose yourself because your biography is still being written. You can't just go to the bookstore and read what your life is going to be like. All we know is that it's going to be an arduous life full of self-doubt and missed opportunities.

And I think Hibana captures that anxiety very well. Amidst all the philosophizing about comedy like the point of originality, the book is really about the sparks of an artist's life in total darkness. This duty to be funny at all costs, to be true to one's art, is exhausting. Sometimes, we don't even see the point. We waddle in the dark, unsure if everything will be okay because no one is laughing with us. People might even think we're boring as hell. And yet, just for a moment, there may be sparks around us but only if we allow ourselves to turn the page of our biographies. This ambiguity scares many people, including myself. I've often wished I knew what I was doing -- and that's why this book resonated with me then and now.

This book captures how I think about the creative process. It articulates my unfounded fears of how I'm bad at expressing myself in a world where manners can change in an instant. The alienation, real or imagined, I feel from people around me when they read or play my stuff makes me want to choke. Sometimes, I have days when I just want to live a "normal" life -- but I can't escape writing. Every time I think I've given up on a writing project, I get a new one in a few weeks. I want to express myself, but I'm afraid of being a failure like Kamiya. Indeed, the whole spoiler section terrifies me because I know I can be awkward around queer people, despite being queer myself. Writing about things like queer literature makes me feel ill because what if I offended someone?

But as the book shows, Kamiya is no failure. He and Tokunaga are still learning and I guess I am too as long as we are alive. Dreams are always worth having if we allow them to adapt. The sparks that inspire us must always be renewed and I think that is the most beautiful philosophy to have about comedy and art.

Extra Notes:

At some point, I'd like to write about the Netflix drama adaptation of this show as it sounds interesting. I'm not sure if this is what my audience would be interested in, so let me know what you think.

There is an English translation of the book with a hideous cover, but I found the translation lacking from the little I read: it leaves out flavorful details (the plywood on top of beer cans just becomes a "makeshift table" as a quick example), and the writing is too literal for the jokes to land. Still, the translation seems to get the general plot. I'm aware that it's unwise to criticize translations in this social media climate, so I'll just say that it's not the worst I've seen -- it's not great either.

[^1]: To be precise, it is marketed as a 純文学 (jyunbungaku) or what we would call high literature in the English-speaking world. This marketing phrase was created in order to distinguish itself from novels that are simply "entertaining". [^2]: 花火 (hanabi) is the word for fireworks and 火花 (hibana) is the word for sparks. Incidentally, Tokunaga's duo is called Sparks in katakana. [^3]: The English translation calls the duo "The Doofuses". [^4]: My favorite detail from the scene is that Tokunaga actually finds pictures of hot naked women and goes, "Oh God, I'm actually doing this for my senpai." I wish I had a kouhai who was like that for me. [^5]: I guess one of the reasons why this scene was so emotional for me is because it reminded me of how Yako's route in the visual novel MUSICUS works as a way out of the music life for the protagonist.